An interest in Victorian serial killers is often viewed by widespread society as an odd and macabre pastime. To demonstrate this, here’s an incident I wrote about in a previous blog which demonstrates how people see you once they discover that you have an interest in such matters. If you’ve read it before I apologise.

In 2001 I was working for an English language teaching magazine based near the University of London. I enjoyed the job, particularly as its location could be reached by bus or bike rather than Tube. I’d cycle a few times a week but, if I was going out after work or had to wear a suit (pleasingly rare), I would take the 38 bus.

One day I was nestled next to the bus window reading Howard Sounes’ book about the Fred West murders. I know, I know. I’m coming to that. Anyway, after a few stops a woman of generous carriage jumped on and decided that the seat next to me was the one for her. I looked up, offered her a weak smile and, this being London, and received a frown by way of reply. Ah well.

Now, I’ll admit here that my own carriage is far from svelte. I am something of a wide gentleman. I am the son of a docker who was himself the son of a docker and am thus broad shouldered by genetic determination. Therefore, this woman was doomed to an uncomfortable journey once she decided that her buttocks should reside next to mine. I shuffled a little, pushed myself into the window and tried not to grunt when she arrived inches from my lap.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, as she grinded into me. I pulled my knees together and tried to find some way of freeing fresh ground as she pushed further. As expected, none was forthcoming. My actions were bootless as I had no territory to cede, but I carried on in the interest of basic manners. This did not satisfy so I tried other ways. My shoulders came next – narrowing to accommodate her own enormous specimens. She began to tut and snort.

‘Sorry, there isn’t much room,’ I replied, nodding at the, shall we say, elephant in the room. We continued with this pantomime for several minutes with no satisfactory outcome. I wondered why she didn’t just give in but then I saw it.

I saw her agenda.

Her plan was to shame me, simply shame me, into relinquishing the window seat and force me into taking her and living with the discomfort of one having one arse cheek hanging over the seat. I was steadfastly against this policy. I stood, or rather sat, firm. My resolve was true. No way, sister.

Back to the book.

She gave up. My inner elbows were touching now and the book was centimetres from my face but I continued reading nonetheless. I had no room at all. I’ve a vague recollection of attempting to use my nose and cheek to turn the page but I couldn’t swear to it. She continued to shoot me aggressive glances but there was no dice.

Then she saw her chance to change tactics. It was a beauty. I’ve got to give her that.

She inhaled loudly while holding her cavernous mouth open and hissing, hissing very loudly I might add…

‘Oh my God!’

I’ll admit that I panicked a bit. Had I nudged her breasts? Touched her buttocks? Difficult not to as they were almost on my hips at this point. What fresh horror was this?

‘Disgusting! Absolutely disgusting!’

Slowly people began to turn around to see what the fuss was about. She was clever. Oh, she was smart. She didn’t voice a direct accusation until the whole lower deck of the 38 to Victoria were paying attention and most of them were agog with curiosity. So was I for that matter.

‘How can anyone read books like that? Revolting!’

Ah, that was it. I was reading a book about a serial killer and that somehow made me equally culpable as West himself. I shrugged and went back to it with an ‘Oh, sod off’ shake of the head. You’ll have to do better than that, love. Pleasingly, the rest of the bus went back to their business of reading papers or listening to music. We manoeuvred through the streets of Islington and I smirked the smirk of the victorious.

I gave her a last look. Her face was almost purple as she was still playing the shame game. I had won, although I was still doing an impression of a battery farm hen. I smirked again; all politeness had long since evaporated.

‘Disgusting.’

I decided not to engage further. I went back to the book but instead of reading I thought about her strategy. Surely this must have been a common occurrence for her. Did she always look for big lads with questionable reading material every day? I released a little giggle at the thought.

‘OH MY GOD!’

What now? I was getting pissed off with this.

‘YOU ACTUALLY FIND IT FUNNY!’

‘No, no! I was laughing at something else,’ my eyes said. ‘I wasn’t…Shit! Did you think I…?’

But no one else was playing now, despite her whirling round for comrades and occasionally elbowing me in the ribs. There were no takers. I was still a bit panicked. What sort of person would laugh at a book like this? I was only laughing at…

Then something bad happened. Something really, really bad.

I realised that someone reading a serial killer book for comic purposes was in itself darkly comical. That made me laugh. Then I remembered that this was the wrong time and occasion to express mirth. I laughed again. And again.

‘YOU THINK THAT FUNNY? DISGUSTING.’

Don’t do it, Karl.

I threw my head back and cackled. Christ, what had I done? She gasped again. I could barely breathe. I did all I could to save myself but I was struggling.

Your mind can be cruel. You can tell it what to do all you like but sometimes it just prefers to play the naughty schoolboy. My shoulders began to shake but my eyes were concentrating on the written word. It made it worse. The woman was now apoplectic.

‘LAUGHING AT PEOPLE DYING’

I roared at that. Absolutely roared. I put my finger on the line so I wouldn’t lose my place when I recovered from the shudders of laughter. It was the worst thing I could have done. It looked like I was saving a salacious death for later reading. The gasps were back too.

‘No, you must stop,’ I begged, as a fresh wave of laughs submerged me.

I was talking to her but it looked like I was addressing the book. Again, that exacerbated the situation, but sensing she had lost, she stood up, called me a pig and went to seek a smaller shouldered man elsewhere. I wiped the tears from my eyes and regained my composure.

I gave that story to Mike, one of the characters in my novel, And What Do You Do, as it sounds better as fiction than fact. The old adage of the difference between the two is that the latter has to make sense is appropriate here, but that story is perfectly true.

During those days my office was next door to a large branch of Waterstones, the booksellers who have recently dropped the necessary punctuation mark from their name – a decision which irks me to this day. A few years earlier my friend Gabrielle worked in that very same shop and told me that the staff would often play a game called ‘Spot the True Crimer’. This would consist of her friends assessing an incoming customer and guessing if they were the sort of people who would walk straight to the True Crime section and seek new books about grizzly deaths or gangland hierarchies. She claims that she never missed. I had a shaved head at the time so I was an obvious candidate.

I deny my membership to that club. I have no wish to collect handguns or daub pentacles on the wall. My interest in the subject is scientific rather than bloodthirsty. From what I can recall about that West book it was mostly about how the media portrayed the case and the knock on effects once the discoveries had been made. Yes, I know something about the murders but not in an appreciative way. I can also speak with some authority about Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, but it is the police ineptitude and diabolical actions of a hoaxer which are more interesting than the man himself. Sutcliffe was a fairly dull individual who got lucky. West was a simpleton who had a ready helpmeet in an evil wife and was also incredibly lucky. Who would want to know about them apart from criminal psychologists? No, it’s the ephemera around them which holds my attention.

And that has been the most rewarding element of the Ten Weeks in Whitechapel series. My plan was to simply write a kind of ‘Ripper 101’ overview and nothing more. I’m not saying anything new about the case – merely putting the basics out there in the hope that others might become as fascinated in it as I am. It’s worked too. I’m answering questions daily now as people have used this column as a launching pad to seek some far off ephemera of their own.

My interest in the Whitechapel murders is from a social history perspective rather than criminology, but if yours is not then that’s fine. Maybe you will have your own curiosities and want to know more about Tumblety, say, or the Maybrick brothers or maybe it is the short lives of the victims and their decline which you find fascinating.

All this is just a warning. People may find you to be a bit weird, particularly if they want your seat on a bus.

But let’s get back to the case and, as I’ve examined those ten weeks in detail, see what happened since the murderer put away his knife and left Millers Court.

To this day the Ripper murders form the greatest whodunit in the history of crime. Only the Kennedy assassination comes close and anyone with a rudimentary knowledge will have a favourite suspect. I speak from experience. When I first began researching the murders I went from Tumblety to Kosminski to William Bury and, although it wasn’t much fun for the poor women involved, it’s easy to spend an hour promoting and debunking theories with like-minded friends.

Such conversations have taken place since the year of the murders itself and modern sleuths have made numerous attempts to unmask the killer once and for all, be it through theory or evidence.

This latter strategy is difficult at best as the surviving papers or any other evidence is scant as much has been lost or stolen/taken as a keepsake over the last century. The ‘Dear Boss’ letter survives to this day but that too was lost for decades. The ‘From Hell’ letter has also disappeared along with various case notes, some of which may well have been vital.

But that’s not to say that discoveries don’t pop up from time to time. The Littlechild letter which heralded the arrival of Francis Tumblety as a potential suspect only came to light in 1987 while the Mary Kelly bed photo only appeared in The Police Journal in 1969 and then in Dan Farson’s book Jack the Ripper in 1972. Maybe, just maybe, there’s an Abberline diary out there somewhere or an irrefutable confession scrawled in a book. After all, secret collectors of Ripperology do exist and occasionally, just occasionally, things are returned to the National Archives or the Black Museum at Scotland Yard. You never know…

But following the Millers Court atrocity and the apparent disappearance of the culprit, the police had no idea what to do next (unless you believe Anderson and Swanson who claimed to have the man locked up). Gradually, the case was wound down and the public were happy at least that the killing had stopped though the lack of an arrest and conviction was frustrating. There was little the police could do given that this was before the age of fingerprinting, DNA and even the preservation of crime scenes.

The police phased down their investigation and Abberline was taken off the case in early 1889 to work on, amongst other things, the Cleveland Street scandal when the police raided an alleged male brothel which may or may not –depending on who you believe- have been attended by the very cream of aristocratic society. Shortly afterwards, on 26th January 1889 James Monro told the Home Office that he would be reducing the numbers of bobbies on the beat ‘as quickly as it is safe to do so.’ The case was as good as over.

There may have been no more murders but the vapours of those ten grim weeks still haunted the public. The political groups considered that, if the police had not arrested anyone it must follow that they knew who was responsible and were covering it up and if that was the case the Whitechapel Fiend must have been someone very high indeed.

Numerous arrests were made but no one was charged.

As the years rolled on the key players in the case began to die off. In 1896, Dr George Bagster Phillips, the Police Surgeon who attended four of the five autopsies as well as three of the crime scenes, died while ‘Leather Apron’ John Pizer succumbed to gastro enteritis in 1897. Three years later, PC Thompson, who nearly caught Frances Coles’ murderer, was killed in a bar room brawl. Dr Thomas Bond, who examined the Kelly body, committed suicide by jumping out of a window. As these people died so did any hope of discovering who did it?

There was one benefit of the case going cold, however. Now that they had retired, several senior officials talked more openly about their time on the case than ever before in autobiographies and memoirs. Sir Robert Anderson brought out The Lighter Side of My Official Life in 1910 while Macnaghten published The Days of My Years four years later. Abberline left nothing behind when he retired as Chief Inspector in February 1892 which was a great shame as no one in the force knew the East End as well as he.

Soon East End mothers, who were once frightened of the murderer, began to threaten their children with him. ‘If you don’t go to bed Jack the Ripper will get you.’ The killer became less of a threat and more of a character – a ghoul, a miasma. This was ‘Gentleman Jack’ with his pantomime villainy bedecked with top hat, bag and gloves. As Bruce Robinson said in his recent book, ‘Jack the Ripper did not look like Jack the Ripper.’

This character grew to such an extent that he soon became fictionalised as the tale and was told time and again in new, exciting ways and media.

The first Ripper related film was released in 1926 in the shape of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog, based roughly on the story of the Batty St lodger, though written Ripper fiction began much earlier. John Francis Brewer wrote The Curse upon Mitre Square as early as October 1888 – merely weeks after the murder of Catherine Eddowes.

The art world also began to take an interest. Ripper suspect, Walter Sickert painted Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom in 1907 and The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do for the Rent? a year later.

(Sickert’s paintings. The latter is eerily reminiscent of the position of Mary Jane Kelly’s body when it was found in Miller’s Court twenty years earlier)

The dawn of modern Ripperology probably began with journalist Daniel Farson’s TV programme Farson’s Guide to the British in November 1959. Farson was something of a trailblazer in terms of modern televisual presentation and chose a much more hard-hitting approach to documentaries rather than the clipped, rather polite, traditional BBC approach. He chose challenging subjects such as mixed marriages and nudism and was not afraid to interview anyone from (to my mind) loathsome right wing extremists such as James Wentworth Day (who thought homosexuals and, by extension, his host, should be hanged) to local vicars in his quest to show a different type of Britain.

It was Farson to whom Lady Christabel Aberconway, the daughter of Sir Melville Macnaghten, showed what may have been an early draft of her father’s now famous memorandum in which he named the three suspects. Lady Aberconway was careful that no one be libelled in the programme so Montague Druitt’s name was abbreviated to ‘MJD’ and it was only in Tom Cullen’s book, Autumn of Terror, in 1965 that Druitt’s name was revealed in full.

For the first time, television had produced fresh interest in the case and, for a while, the Whitechapel Murders were in vogue once more.

The most famous Ripper film of the 1960s was not fictitious at all but a strange, quirky documentary called The London Nobody Knows in which the actor James Mason walks around the capital looking at peculiar people and practices. Near the end of the film he visits 29 Hanbury St, knocks on the door and asks a rather bemused resident if he can take a look around. He stands in the yard, pointing at the murder site with his walking stick and tells us that this is where Jack did his work. Though he fails to name Annie Chapman. There then follows a trip around the area including footage of drunks fighting in Brick Lane, a tramp looking for scraps in a deserted Spitalfields Market and some hopeless inebriates in Itchy Park – the grounds of Christ Church near the Ten Bells pub.

(James Mason walks past the spot where Annie Chapman’s body was found in 1888, between the door and the fence behind him)

It is the best footage we have of that area before the house was torn down in the early 70s to make way for the Truman brewery. The film is available on DVD and, trust me on this, it’s really, really odd. I love it.

1970s Ripperology was dominated with the Royal conspiracy thanks to the Barlow and Watt programme and Stephen Knight’s book (see last week’s article). It was also a great time for Ripper fiction. There had already been a rather misogynistic episode of Star Trek in 1967 entitled Wolf in the Fold which bore some Victorian/Whitechapel hallmarks but in 1979 the tale was also adapted for the big screen with Murder by Decree starring Christopher Plummer and, him again, James Mason as Holmes and Watson as they attempt to catch the murderer.

The area itself, with some of the Victorian streets and buildings still relatively unchanged began to cash in on the case. In 1976, the Ten Bells pub, where Kelly and Chapman may have drank on the night of their murders, took the extraordinary decision to change its name to ‘Jack the Ripper.’ Even before taking in account the historical nature of its original name (it has been there since the 1750s and is thus one of London’s oldest pubs), naming it after a slayer of women was tawdry to say the least and, as with many things Ripper related, the murderer appeared to be celebrated for his deeds by way of recognition. Fortunately, following a campaign by the group ‘Reclaim the Night’ amongst others, the brewery saw sense in 1988 and changed it back.

(Jack the Ripper pub photo courtesy of Neil Bell)

Incidentally, the celebrity chef Jamie Oliver claims that his great-great grandfather was the landlord of the pub in the 1880s. If true, he may have served the killer.

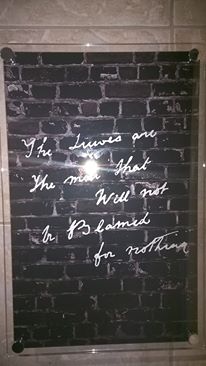

Today, the East End seems rather coy about its infamous resident as there is little to point out what happened where. The White Hart pub has a plaque suggesting that George Chapman, who once worked in the basement, placed outside its side entrance in Gunthorpe Street while there currently sits a mock Goulston St Graffito a few yards up the road. There is also a window of Ripper artefacts (copies of the ‘From Hell’ letter, pictures of the suspects etc.) opposite the pub but that seems to be the only mention of the murders in the area.

The murder sites themselves are fairly nondescript locations. A few years ago somebody placed small plaques around the sites, claiming them to be ‘Mary Ann Nichols Row’ etc., though none exist today. The only thing similar is a stencilled graffito on Henriques Street about 100 yards from Elizabeth Stride’s murder site.

In fact, access to the majority of the sites is restricted these days. Bucks Row/Durward St is now a construction site with Polly Nichols’ site frustratingly out of reach on the other side of a fence – pictured below. I was too much of a coward to take a picture over it but my friend Jane had no such qualms as she held her camera high and snapped indiscriminately. She got lucky with this picture as the orange box marks the murder site of Polly Nichols.

(Photo: Jane)

29 Hanbury Street is now a private car park which doubles as a market at the weekend. The houses have long since been demolished so it’s difficult to earmark the exact spot. It’s roughly where this green light appears.

The murder location of Liz Stride at what was once 40 Berner St is now a school so photography is obviously impossible at times. However, you can still see the place. She would be facing us in this pic along the closer of the yellow lines.

Mitre Square is undergoing a major development though it currently remains the only site where you can stand on the exact position on any given day (though please don’t do that).

That said it’s not certain just how long that will be there as there are plans to build a ‘Public Realm Enhancement’, whatever one of them is, there. I suspect it will do little to help Ripperologists and walking tours. Mitre Square was once full of Ripper tours (I counted six one night) but now it is more or less empty as it becomes smaller and smaller. Nevertheless, you can still visit the spot where Joseph Lawende saw Catherine Eddowes talk to a man in what was once Church Passage, though that too is subject to eternal roadworks and developments.

S

As for Millers Court/Dorset St – just forget it. Seriously, don’t bother. It’s now in the middle of a building site somewhere opposite Christ Church, Spitalfields. It was once a service road to the north of where Whites Row car park – a 1970s eyesore – before that too was demolished. In any case the entire area is walled off while construction work goes ahead.

There is better news in Goulston St. The place where the apron and graffito were discovered in remains though the stairs have gone. It now forms the doorway of the ‘Happy Days’ chip shop. The owners have even been good enough to put a photo up of roughly where the words were scrawled.

(Erm, not genuine, obviously)

‘Happy Days’ have a restaurant area to the left of the takeaway chip shop which has several pictures of suspects and people of note on the walls and it’s not often you get too sit and eat fish and chips under the watchful gaze of Sir Charles Warren.

The owners don’t mind you taking photos and there’s also a well-written primer about the murders on their website. Some may see this as exploitative but I’d rather spend time in a place called ‘Happy Days’ than ‘Jack the Ripper.’

There is a local barbers nearby called ‘Jack the Clipper’ but that’s as close as the East End comes to mentioning the Whitechapel murderer save for the numerous Ripper tours which scurry around Spitalfields and Aldgate East at night.

Some think that the area should do more to show its dark history and even preserve some of the sites, but there’s little coin to be made from pointing out where a famous murder took place. In any case, the number of Ripper tourists has never declined so you have to admire the area’s restraint into not turning it into a sort of serial killer’s Disneyworld.

So why has this series of murders lasted so long in the public conscience? After all, there are far grislier slayings and serial killers with a higher murder count than five both before and since the case. Peter Sutcliffe killed at least 13 women and attacked many more. Furthermore he had a similar desire to mutilate women but, to my knowledge, there are no Yorkshire Ripper tours.

You could argue that it is because ‘Jack’ was never caught but there are still mysteries in other cases. There is a still a missing body in the case of the Moors Murders but will that be remembered in 130 years even though child murder is more hideous than any other crime? I doubt it.

Any view is valid of course, but I suspect it’s because we have so little to go on. This man walked around the busiest neighbourhood of the busiest city of the world, viciously killing women on the streets with others nearby -to such an extent that on two occasions he slayed his prey outside buildings where a twitching curtain would have done for him- and no one saw a thing. In Mitre Square he killed and disembowelled Catherine Eddowes in between the beats of two policemen and still walked away. The audacity of the murders – the silence and vanishing acts – makes him appear superhuman.

He was actually anything but. He was simply an incredibly lucky man. He wasn‘t a genius or criminal mastermind or protected or anything similar. He should have been caught but the times were in his favour. Had it been today Annie Chapman, Liz Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Kelly may well have survived.

So who was he? Do we have any idea at all?

During the Yorkshire Ripper murders one of the investigation rooms had a blackboard with two sentences written upon it divided by a vertical line. One side said ‘What we think we know about the Ripper’ with a list of bullet points underneath. The other ‘What we actually know.’ There was nothing underneath those words. This is not strictly true with the Whitechapel case. Despite an absence of evidence there are things we know about the killer.

Firstly, he was a local or at least dressed as one, and, if witnesses can be believed, (ignoring Matthew Packer and George Hutchinson) was foreign/Jewish. That last statement isn’t based on any casual racism as was customary in 1888, but on Mrs Long’s testimony, as she certainly saw Annie Chapman with the wanted man. The broad shouldered man who attacked Liz Stride in Berner St used an anti-Semitic remark to Israel Schwartz or ‘Pipe Man’ so we could suppose he wasn’t Jewish, but it is far from a certainty that Stride’s killer was actually the Ripper.

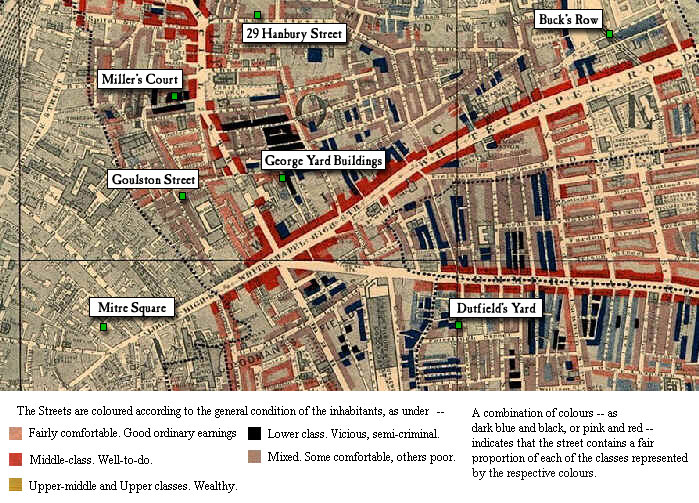

What else do we know about him? Well, he knew the East End. As stated earlier, he ran from Mitre Square and disappeared into thin air. He walked away from Mary Kelly’s room and into one of the most densely populated streets in London and no one saw a thing. This suggests a bolthole nearby. Somewhere where he could lock a door and be at one with his ‘trophies’. The night of the ‘double event’ was the only occasion where we know roughly where he went following a crime. He was headed towards Goulston St – a stone’s throw from the rookeries of Dorset St, Thrawl Street and Flower and Dean Street – once he had finished with Catherine Eddowes. He did not jump into a carriage and jet off to the Inner Temple or the more salubrious domiciles of the West End. He walked into the East End and it’s not unreasonable to presume that it’s because he lived there.

We also know his killing ground. He didn’t like to travel.

It is possible to walk from the most westerly murder – Mitre Square – to Bucks Row in the east in about twenty minutes. In terms of tube stations, Aldgate East, next to the Martha Tabram and Spitalfields murders, is one stop away from Whitechapel while Aldgate –the station closest to Mitre Square is only a three minute walk to Aldgate East. In fact, I’ve just used an online map and plotted a direct course from Bucks Row to Mitre Square passing down Whitechapel High Street, Aldgate High Street and Mitre St and it comes up with 0.92 mile! It’s unlikely that someone would travel any great distance to murder on four different nights when there was hardly a paucity of prostitutes in other parts of the East End. No, the killer was local.

So, male, foreign and local. That narrows the field down to around 60,000 people – many of whom used assumed names. We (don’t especially) progress, Watson!

Since we’re discussing the local topography I might as well share this. I recently came across a You Tube documentary about Stephen Knight’s royal conspiracy theory which showed an extraordinary map of 1888 Whitechapel. Let’s just say that the cartographer was a fan of Picasso or William Burroughs ‘write things down, jumble them up and tape them back together’ method of writing which was so admired by David Bowie et al.

Here’s the real map.

Sorry. That’s always made me laugh.

He may have had some rudimentary anatomical knowledge though no one is certain. He did know the method of cutting a throat while avoiding blood stains. He cut from left to right probably by standing behind his victim (Nichols had thumb marks on her face where he had held her steady to afford a grip). By strangling his victims until they lay on the floor before severing the left carotid artery, he could avoid the blood. Had it been a straightforward slash he would have been covered in the stuff. He knew that and this suggests that, at the very least, he knew a little of butchery. He may well have worked in a profession where blood stains were not uncommon and could walk around the streets of E1 without attracting suspicious.

Male, foreign, local, knew about butchery.

Okay, we can’t arrest anyone yet but there are a few facts about him. It’s just a shame it’s not enough.We’ll never know who did it. Ever.

But sometimes that’s the best part.

POSTSCRIPT

That concludes the Ten Weeks in Whitechapel series. I’ve enjoyed writing this series and there are plans afoot to find it a more permanent home than on these pages. Watch this space.

I may return with the odd blog should something happen – be it evidence or an insatiable need to write more about my favourite topics. I’d like that.

It just remains for me to thank everyone for reading and providing questions for the Q&A. I’d also like to thank Martin Fitzgerald for shouting ‘Do it!’ when I suggested the series to him, for Serena Casey for looking stern when needed, Devlin Macgregor, Sue Hayrettin, Cate and Jane Hall for dragging them around the streets and babbling on about autopsy reports, as well as Ripperologists who have been kind enough to answer my questions and send photos – namely Jonathan Menges, Neil Bell, Jon Rees and Philip Hutchinson. We may never learn the man’s identity, but the history of the Whitechapel murders is educational and, as Holmes tells Watson in His Last Bow:

“Education never ends, Watson. It is a series of lessons,, with the greatest for the last.”

Thank you.

Karl Coppack, April 2017

Karl, a great article. I know a family that lived at 29 Hanbury Street, shortly before it was demolished. Love your writing style. All the very best.

Mike Levy.

LikeLike

Really? The same woman who answers the door in the film?

LikeLike

No, i don’t believe so. Her parents kept the fact about what happened in her backyard a secret from the kids. It wasn’t until years latter that she found out. She has vivid memories of playing in the yard, where Annie Chapman wad so brutally murdered. She lived on the upper floor of the building.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Someone took over Mary Kelly’s room too!

There was a murder committed a few years later in the room above.

LikeLike

No, i don’t believe so. Her parents kept the fact about what happened in her backyard a secret from the kids. It wasn’t until years latter that she found out. She has vivid memories of playing in the yard, where Annie Chapman was so brutally murdered. She lived on the upper floor of the building.

LikeLike

The beauty of this subject is that we very unlikely to know who the culprit was. Therefore writers can endlessly speculate without being positively proved wrong.

LikeLike